Pat O’Donnell, field crew chief, prepares a drilling fluid (made of clay and water) at a geotechnical drilling site near Hwy 60 in St. James. The fluid, pumped into a drilled hole in the ground, keeps the hole from collapsing once groundwater is reached. MnDOT staff photo |

By Joseph Palmersheim

Rich Lamb says there is a classic joke at geotechnical engineering conferences that is often used to start a presentation: “If you look up the word ‘boring’ in the Yellow Pages, the entry reads, ‘See geotechnical engineers.’”

From Lamb’s point of view, geotechnical engineering is “probably anything but boring.” Quite the opposite, actually.

“I don’t think I could have found a more interesting job at MnDOT,” he said.

Lamb, state foundations engineer, is one of 14 people assigned to the Foundations Unit of the Geotechnical Engineering Section, which is part of Office of Materials & Road Research in Maplewood. These employees perform a variety of tasks including field work, laboratory testing and engineering analyses. They take a good look at the earth to determine if the soils are capable of supporting bridges, retaining walls, large drainage structures and other transportation-related structures.

“You need to investigate what’s underground,” Lamb said. “Say we’re building a new road somewhere, and you didn’t do an investigation before you place a 25-foot embankment. If the site contained poor soils, you’d at a minimum have settlement problems, and the pavement would have to be replaced much more frequently. As another example, bridges can be supported on deep driven piles or on shallow-spread footings. That’s the main thing – which will we use? If we choose deep-driven piles, the Bridge Office will want to know how long they’ll be, to estimate cost. If a standard bridge costs $1 million, foundations can cost up to $50,000.”

Foundation Unit field crew workers drill into the ground to gather soil and rock samples, which are classified and tested for strength and compressibility in the Foundations Unit lab.

These crews work on the road from Monday to Thursday, traveling wherever their services are needed and working year-round in all types of weather. In a typical year, they’ll work on 12-15 bridge projects, 20-25 culverts, and other miscellaneous work. It’s a skill that’s needed for something as small as a culvert or as large as the Interstate 35W@94 project.

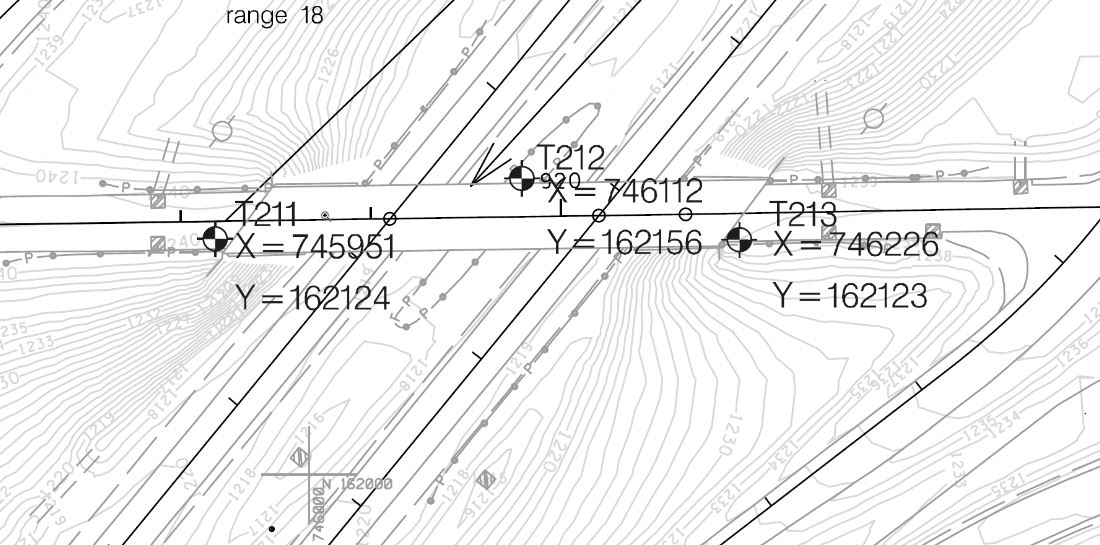

X marks the spot: Drill crews are given GPS coordinates like these to show exactly where on a site to drill. The average bore hole for bridge investigations is around 75 feet, and some go as far down as 150 feet. MnDOT staff photo |

The first step is knowing where to drill.

Geotechnical engineers choose where borings and samples are needed. Drill crews are given GPS coordinates, and any site utilities are marked by Gopher One before the crews starts drilling.

The average bore hole for bridge investigations is around 75 feet, Lamb said, and some go as far down as 150 feet.

“We sometimes have to set up the drill rig in very difficult terrain,” Lamb said. “Our drill rigs are tracked, like a tank, and they can go most anywhere, except really steep slopes. Normally, we’ll be using a lot of drill rods to get deep enough. The main purpose is to get samples back so you can test and classify them.”

A 50-foot boring can take a day or day and a half. A lot of this time is spent getting to the site and setting up. The drilling doesn’t take too long. Depending on conditions, crews can go through 10-20 feet of soil an hour. Rock drilling is much slower.

To retrieve a soil sample, field crews use a hollow 18-inch-by-2-inch cylindrical sampling tube called a split spoon sampler, similar to those in use for the past 100 years. Once the desired sample depth is reached, the drilling stops, and the sampling tube is hammered into soil as part of standard penetration test. This gives an idea as to the soil’s density (with the number of hammer blows per foot) and also fills up the sample tube.

Sampling bedrock is quite different. The rock must be cored using a rotating sharp-edged sample device called a core barrel. While it may seem counterintuitive, it’s easier to core through hard rock like granite, Lamb said, because the material stays more intact than softer, less cemented, rock like sandstone.

And naturally, the earth doesn’t always cooperate with someone trying to drill a hole in it. To keep bore holes from collapsing, especially below the groundwater table, drill crews use a drilling fluid (a mixture of natural clay and water) that is pumped into the borehole to keep it from closing. This requires water, which the crews have to bring with them.

“In addition, anytime we drill, we have to submit a record to Department of Health showing that we sealed the hole, and that it’s not hollow,” Lamb said. “They don’t want contaminants getting into the ground.”

While each district has capacity to do shallow roadway boring for pavement investigation, they use smaller drill rigs and different drilling equipment, typically drilling less than 10 feet down, looking just below the pavement. With geotechnical drilling, MnDOT crews go down much deeper, sometimes through millions of years of sediment.

“You have to think about the glaciers that covered the state more than 10,000 years ago,” Lamb said. “The glaciers did a lot of the depositing of soils and scouring, and the bedrock was here before that. I’ve learned a lot about geology during my career. Sometimes you find cow bones. I think we found a piece of pottery once. You’ll find layers of wood. Once, while working on the St. Croix River Crossing project, we found thick layers of wood and sawdust, and it turns out there had been a lumber mill where we were drilling.”

Nearly 30 years into his career with MnDOT, Lamb is still learning new things about drilling and geotechnical engineering. Even as a child, he had a strong interest in exploration and discovery.

“We don’t know what’s below the ground. That’s fascinating to me - that we can move out to a site and return some soils and show people what we found, which can affect how a bridge is designed and built. It’s overwhelmingly satisfying.”

|